Volume 10 of the Béla Bartók Complete Critical Edition series, containing all folk song arrangements for voice and piano, was published in November 2024. By bringing together all these works, the volume provides a unique overview of the genre that played such an important role in Bartók’s workshop, and of its stylistic changes. The exceptionally broad timeframe of the compositions in this volume is also telling: the earliest piece coincides with Bartók’s first folk song experience of decisive importance (Székely Folk Song, 1904), while the latest can be dated to the year of his death (Three Ukrainian Folk Songs, 1945). Another peculiarity of the volume is, however, that it brings to light several works unpublished in Bartók’s lifetime or previously unknown versions, thus providing a new and highly nuanced picture of the genre in Bartók’s works.

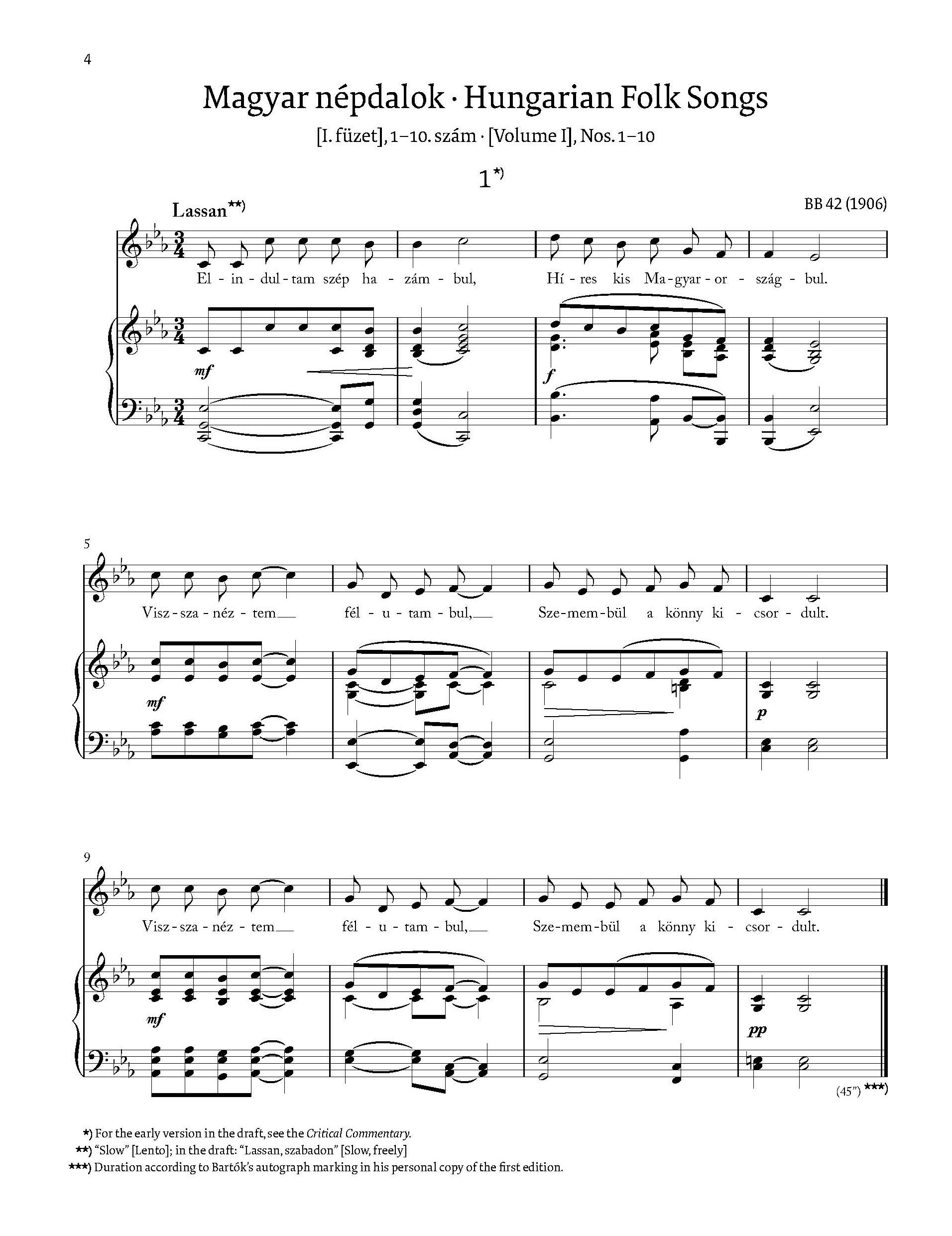

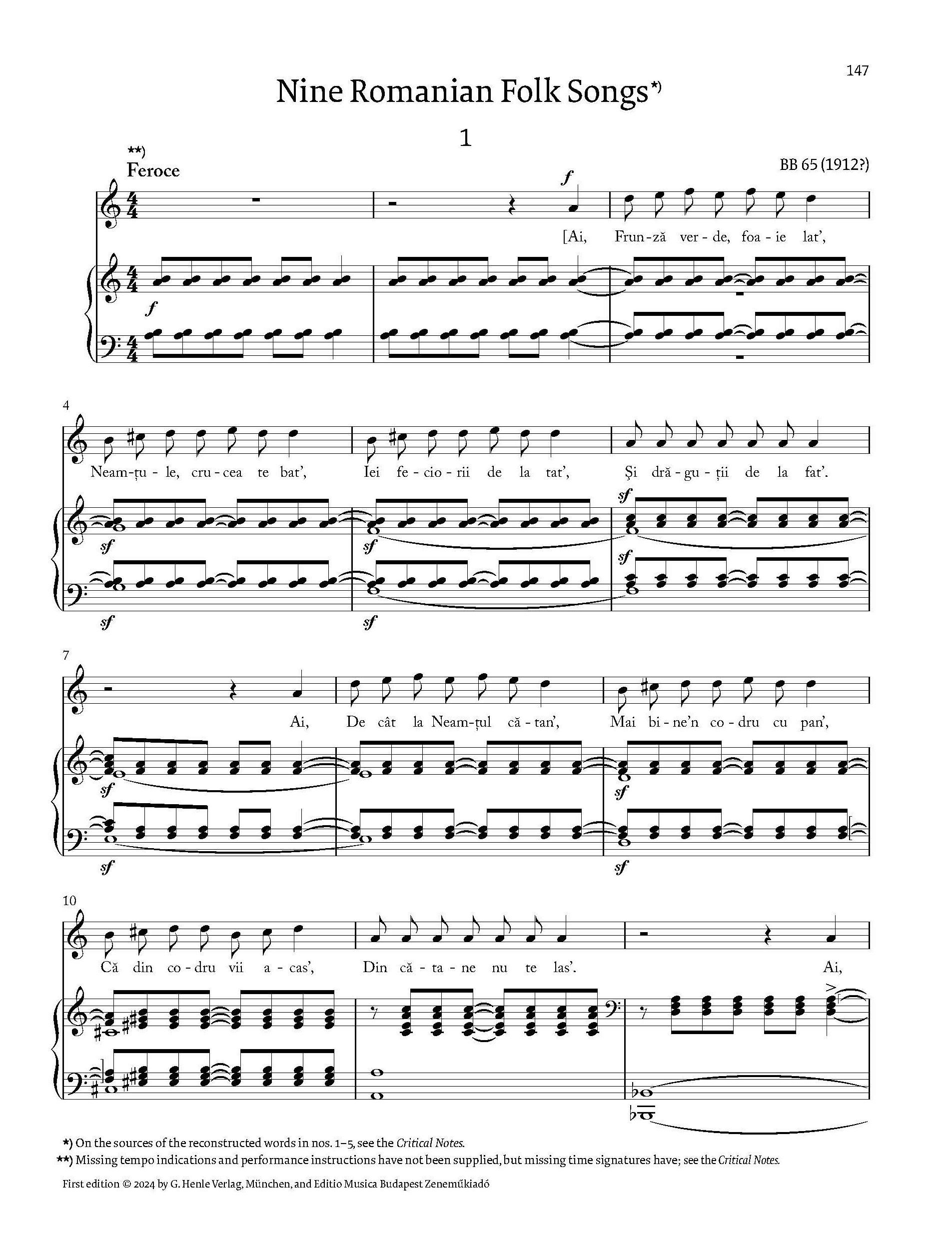

The volume, edited by Vera Lampert, with the collaboration of Viola Biró, contains seven compositions in its main part, including such well-known works as Eight Hungarian Folk Songs, Village Scenes based on Slovak folk songs, Twenty Hungarian Folk Songs, and the Bartók pieces of the Hungarian Folk Songs published jointly by Bartók and Kodály in 1906. (This last mentioned set is presented in two versions: the first edition, and the last revised edition.) On the other hand, the works published in the Appendix are largely new: some eight works that remained in manuscript (complete but unedited sets – including a previously unknown set of nine Romanian folk songs –, occasional arrangements, and unfinished or fragmentary works), and some versions of well-known pieces, are partly published here for the first time. While these unpublished works, mostly from the period of Bartók’s folk song collections, reveal the close links between Bartók’s compositional work and his folk music research, the variants give an idea of the diversity of folk song sets, which reflect their special purpose. An important example of the latter is the three different selections from the early joint volume by Bartók and Kodály: the published original version dedicated for amateurs (Hungarian Folk Songs, BB 42, 1906), Bartók’s own concert version from the same period (Four Hungarian Folk Songs, 1906), and, finally, the version recorded on a disc some twenty years later (Five Hungarian Folk Songs, BB 97, 1928).

The volume also contains a wealth of textual material. The score is accompanied by a detailed Introduction – in three languages – on the genesis, performance and reception history of each composition, followed by a chapter on Bartók’s notation and specific questions of performance. The second part of the Appendix contains literal English translations of the song texts. Finally, the volume concludes with Critical Commentaries on the compositional sources of the works, sometimes with detailed discussions of their genesis, and with transcriptions from compositional manuscripts – above all, the complete draft of Twenty Hungarian Folk Songs.

Viola Biró

|

|